Outside the Garden Wall

|

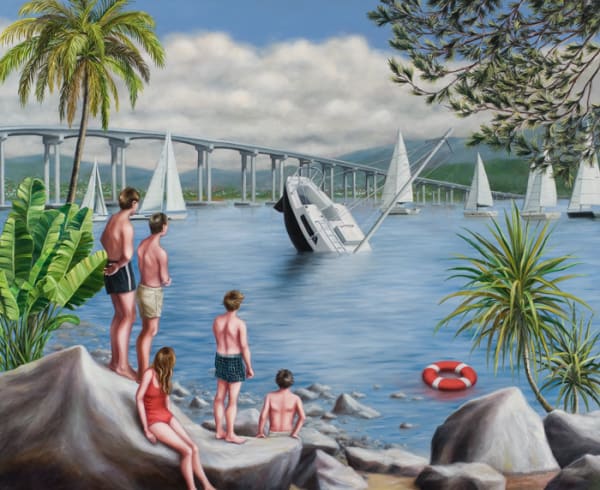

They unfortunately could never be postcards: Amber Koroluk-Stephenson’s visions of the Australian landscape are picturesque, however the animating principle is a psychological undercurrent of melancholy, absence and displacement.

A conversation, not immediate or immediately observable, has taken place across a long-format time scale in Australian painting. Koroluk-Stephenson is the most recent interjection to this discussion. From 1788 to the present, non-Indigenous Australians have sought to reconcile themselves with the Australian continent and its unique and bizarre conditions. In transplanting the means and methods of European art into an environment so alien, landscape painters grasped for visual vocabulary worthy of their surrounds and continue to do so: These concerns did not benefit from syncretism with Indigenous knowledge, particularly in Tasmania, whose history is writ large, for a state so small.

Contemporary relationship to the land can be seen in many incarnations: The primary terms ‘bush’ (1) and the ‘outback’ we use to describe our natural world comprise a lexicon so sparse and unforgiving towards the land, that clinging perilously to the coastline seems a reasoned choice for most Australians. Such a limited vocabulary is symptomatic of the history of the nation—Horace Watson’s wax cylinder recordings of Fanny Cochrane Smith hauntingly hold onto the last fluent words of a language that would have been wholly shaped by Tasmania (2).

Beyond the Garden Wall is where Koroluk-Stephenson wanders into the uncharted, trying to reanimate the vocabulary lost to modern Australia. These sublime, arresting and tacit paintings converse with her antecedent, John Glover, whose depictions provide us with the opening remarks of the discussion: His paintings have been lambasted as awkward, “the foreground trees flat and unreal” (3), as he sought to develop a visual vocabulary to describe his surroundings. In much the same way Glover’s son, travelling to Tasmania by ship, described dolphins as “like a broad thick eel” as he came to terms with the unknown (4).

In light of this, Koroluk-Stephenson employs language such as stranded, foreign and sinking, a seemingly intergenerational dialogue with McCubbin’s Lost and Jane Sutherland’s Obstruction. Her visual vocabulary is equally as exploratory with puzzling artefacts and anonymous denizens populating her landscapes. Just as Koroluk-Stephenson deftly interrogates this relationship to the environment around us, ground-breaking research by Bill Gammage is revising our perceptions of the Indigenous relationship to land: revelations that the Australian landscape may not have been a wilderness, but a managed, cultivated environment worthy of the term ‘estate’ in his book The Largest Estate on Earth. This body of research draws its insights partly from written and environmental records, but also from landscape paintings such as Glover’s.

As our presumptions are cleaved in two, Koroluk-Stephenson presents a duplicitous view with Foreign Object I and Foreign Object II. Both images, viewed together, present a wilderness and a controlled environment, equally romanticised, yet posing the question: On what side of the garden wall does civilisation lie?

David Greenhalgh, March 2016

1 Bush as we use it in Australian English most likely derives from the Dutch bos, denoting land to 2 The Palawa Kani project does, however, hope to revive this fluency. 3 McPhee, J. (1980). The art of John Glover, Artarmon: MacMillan. p. 37-38 4 Ibid. p. 53 |

-

Amber Koroluk-StephensonParadise Dreaming, 2015oil on canvas150 x 300 cmSold

Amber Koroluk-StephensonParadise Dreaming, 2015oil on canvas150 x 300 cmSold -

Amber Koroluk-StephensonAppreciation Society, 2016oil on canvas112 x 153 cmSold

Amber Koroluk-StephensonAppreciation Society, 2016oil on canvas112 x 153 cmSold -

Amber Koroluk-StephensonPretend the Ship’s not Sinking, 2016oil on canvas112 x 137 cmSold

Amber Koroluk-StephensonPretend the Ship’s not Sinking, 2016oil on canvas112 x 137 cmSold -

Amber Koroluk-StephensonAll the Way to the Bottom, 2016oil on canvas97 x 153 cmSold

Amber Koroluk-StephensonAll the Way to the Bottom, 2016oil on canvas97 x 153 cmSold -

Amber Koroluk-StephensonAdrift, 2016oil on canvas81.5 x 148.5 cmSold

Amber Koroluk-StephensonAdrift, 2016oil on canvas81.5 x 148.5 cmSold -

Amber Koroluk-StephensonStranded, 2016oil on canvas81.5 x 148.5 cmSold

Amber Koroluk-StephensonStranded, 2016oil on canvas81.5 x 148.5 cmSold -

Amber Koroluk-StephensonForeign Object I, 2016oil on canvas97 x 122 cmSold

Amber Koroluk-StephensonForeign Object I, 2016oil on canvas97 x 122 cmSold -

Amber Koroluk-StephensonForeign Object II, 2016oil on canvas97 x 122 cm

Amber Koroluk-StephensonForeign Object II, 2016oil on canvas97 x 122 cm