In a Strange Land

I’ve been wanting to learn Persian miniature painting for about 10 years now and I began to realise that the likelihood of ever being able to go to Lahore, Pakistan seemed to be receding further and further into the distance. So I went to London instead. I thought I was going there to learn a technique that I could adapt to my abstract and sensory interpretations of light and air in the landscape - a kind of ‘micro world’ of tiny shimmering lines. As it turns out the process of learning Persian miniature painting involves studying the original masters and doesn’t allow for a great deal of personal invention or self expression. It makes sense really, how else do you perfect the skill of using such a tiny brush, make paints from traditional pigments and understand the aesthetics of a cultural tradition that dates as far back as the 12th Century CE. The process of learning is understandably slow and very meticulous and has involved considerable amount of research into Islamic art and aesthetics. So I have put aside my 21st century Western understanding of contemporary abstraction for just a moment and stepped back a few centuries to explore another aesthetic world from an entirely different culture to my own, which will bring new insights and possibilities to my painting practice. Although the outcome of this new work appears so clearly different to what I have done in the recent past, many of the concerns relating to the landscape and how we perceive it remain continuous.

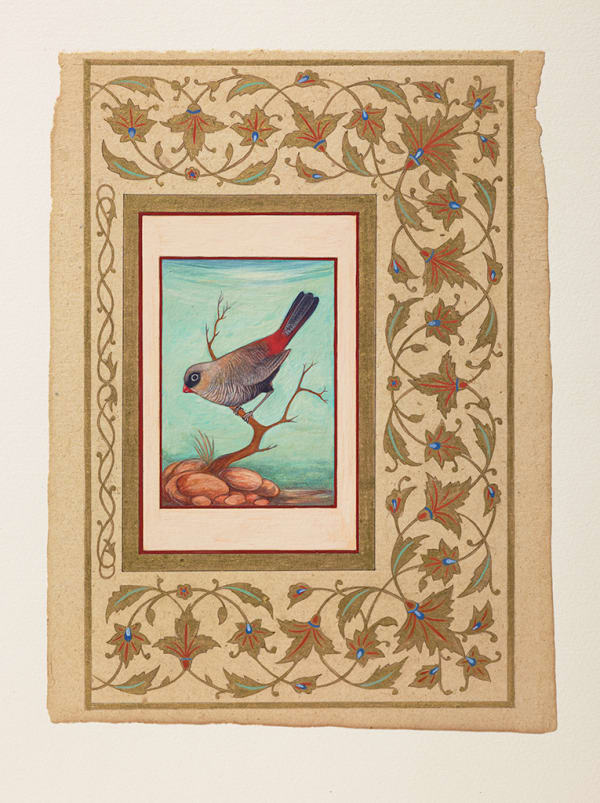

This series of manuscript paintings is loosely based on the traditions and aesthetics of both Persian and Mughal manuscript painting. The starting point is a painting by Habiballah of Sava , (ca 1600 CE, Isfahan, Iran) of the Mantiq al-tayr (The language of the birds). This folio illustrates a masnavi or a poetic text of the same name (also often referred to as The conference of the birds) by Farid al-Din Attar (ca 1187 CE ). The story comprises of a series of parables narrated by the Hoopoe who leads a group of birds on a journey to seek a new leader. It is a difficult journey and after many challenges along the way only 30 birds arrive at their destination, the home of the Simurgh, a mythical Persian bird. When the birds finally arrive at the dwelling place of the Simurgh, all they find is a lake in which they see their own reflection. The story is an allegory of the challenges of the journey through life, self-realisation and transcendence of the everyday world.

In my adaptation of the ‘Language of the birds’, I have reinterpreted the narrative into the landscape and birds of Tasmania. For me the painting now also tells a story about the challenges that human beings present for the survival of the natural world around us and our need to care for it. It is also about how our understanding of birds helps establish relationships and a sense of connection to the environment.

Interestingly, through my study of Persian and Mughal manuscript painting I found a tradition of natural history painting of birds from the 16th Century, painted with such lyricism and delicateness equal to the more widely known subjects of portraits of emperors and epic narratives of love and war. In a great leap of the imagination I have linked these Persian natural history paintings with Australian colonial natural history paintings of the first fleet: Thomas Watling, the Sydney Bird Painter and other ‘Unknown’ artists, to tell a story of ‘The language of the birds’ as I perceive it in Tasmania. I imagine myself to be in another time, arriving on the shores of Tasmania by ship a few centuries ago, discovering and understanding these birds as if for the first time. Only the landscapes have changed, these are not the forested landscapes of pre-settlement in Tasmania. The trees resemble the dead trunks that can now be seen on Midlands highway and the land has been denuded, over grazed and felled. The birds have become refugees to the effects of climate change and human settlement encroaching on their habitat as they find themselves trying to adapt to new and strange landscapes.

This series of manuscript paintings evolved from these two disparate but strangely similar traditions of natural history painting from two entirely different cultures; 12 -16th Century Persia and 18th Century colonial Australia. I have adapted and incorporated my vision of birds that I know and have strong relationships with from my home in rural Tasmania, into the contexts of Persian and Mughal miniatures that celebrate birds while telling a story of threat and optimistic survival.

SueLovegrove Jan2016

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks to Dr Sally Bryant for sharing her passion and knowledge on birds and bird calls. Thanks also to Al Wiltshire for teaching me about the birds that inhabit my place over many years. And thanks to Ron Nagorcka for giving kind permission to play “Life on Black Sugarloaf” from his Cd “Secret Places” during the exhibition.

-

Sue LovegroveCommon Bronzewing, Phaps chalcoptera, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxAU$ 2,200.00

Sue LovegroveCommon Bronzewing, Phaps chalcoptera, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxAU$ 2,200.00 -

Sue LovegroveSpotted Turtledove, Streptopelia chinensis, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxAU$ 2,200.00

Sue LovegroveSpotted Turtledove, Streptopelia chinensis, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxAU$ 2,200.00 -

Sue LovegroveBrush Bronzewing, Phaps elegans, 2015(After unknown Australian artist, 1788-99, Lambert’s Derby Collection)

Sue LovegroveBrush Bronzewing, Phaps elegans, 2015(After unknown Australian artist, 1788-99, Lambert’s Derby Collection)

watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxAU$ 2,200.00 -

Sue LovegroveYellow Wattlebird, Anthochaera paradoxa, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold

Sue LovegroveYellow Wattlebird, Anthochaera paradoxa, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold -

Sue LovegroveShining Bronze Cuckoo, Chrysococcyx lucidus, 2015(After Sydney Bird Painter, 1792, Australia)

Sue LovegroveShining Bronze Cuckoo, Chrysococcyx lucidus, 2015(After Sydney Bird Painter, 1792, Australia)

watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approx -

Sue LovegroveFan-tailed Cuckoo, Cacomantis flabelliformis, 2015(After Sydney Bird Painter, 1792, Australia)

Sue LovegroveFan-tailed Cuckoo, Cacomantis flabelliformis, 2015(After Sydney Bird Painter, 1792, Australia)

watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxAU$ 2,200.00 -

Sue LovegroveSpotted Quail-thrush, Cinclosoma punctatum, 2015(After Sydney Bird Painter, 1792, Australia)

Sue LovegroveSpotted Quail-thrush, Cinclosoma punctatum, 2015(After Sydney Bird Painter, 1792, Australia)

watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approx -

Sue LovegroveGrey Shrike-thrush, Colluricincla harmonica, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold

Sue LovegroveGrey Shrike-thrush, Colluricincla harmonica, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold -

Sue LovegroveHoopoe, Upapa epops, 2015(After Ustad Mansur, 1590-1624 Mughal)

Sue LovegroveHoopoe, Upapa epops, 2015(After Ustad Mansur, 1590-1624 Mughal)

watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxAU$ 2,200.00 -

Sue LovegroveWhite-breasted Sea Eagle, Haliaeetus leucogaster, 2015(After unknown Australian artist, 1788-99, Lambert’s Derby Collection)

Sue LovegroveWhite-breasted Sea Eagle, Haliaeetus leucogaster, 2015(After unknown Australian artist, 1788-99, Lambert’s Derby Collection)

watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold -

Sue LovegroveWhite Goshawk, Accipiter novaehollandiae, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approx

Sue LovegroveWhite Goshawk, Accipiter novaehollandiae, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approx -

Sue LovegroveForty-spotted Pardalote, Pardalotus quadragintus, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold

Sue LovegroveForty-spotted Pardalote, Pardalotus quadragintus, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold -

Sue LovegroveCrescent Honeyeater, Phylidonyris pyrrhoptera, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold

Sue LovegroveCrescent Honeyeater, Phylidonyris pyrrhoptera, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold -

Sue LovegroveTasmanian Native Hen, Gallinula mortierii, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approx

Sue LovegroveTasmanian Native Hen, Gallinula mortierii, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approx -

Sue LovegroveSpur-winged Plover – Standing on the World, Vanellus miles, 2015(After Port Jackson Painter 1788, Australia)

Sue LovegroveSpur-winged Plover – Standing on the World, Vanellus miles, 2015(After Port Jackson Painter 1788, Australia)

watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold -

Sue LovegroveRufous Night Heron, Nyticorax caledonicus, 2016(After Ustad Mansur, 1590-1624, Mughal)

Sue LovegroveRufous Night Heron, Nyticorax caledonicus, 2016(After Ustad Mansur, 1590-1624, Mughal)

watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold -

Sue LovegroveAustralasian Bittern - Holding up the sky over Egg Islands, Botaurus poiciloptilus, 2016(After Thomas Watling, 1792, Australia)

Sue LovegroveAustralasian Bittern - Holding up the sky over Egg Islands, Botaurus poiciloptilus, 2016(After Thomas Watling, 1792, Australia)

watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold -

Sue LovegroveWhite Faced Heron, Egretta novaehollandiae, 2016watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold

Sue LovegroveWhite Faced Heron, Egretta novaehollandiae, 2016watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold -

Sue LovegroveEastern Curlew, Numenius madagascariensis, 2015(After Unknown Australian Artist, Lambert’s Derby Collection 1788-99)

Sue LovegroveEastern Curlew, Numenius madagascariensis, 2015(After Unknown Australian Artist, Lambert’s Derby Collection 1788-99)

watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxAU$ 2,200.00 -

Sue LovegroveDusky Robin, Melanodryas vittata, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold

Sue LovegroveDusky Robin, Melanodryas vittata, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold -

Sue LovegroveBeautiful Firetail, Stagonopleura bella, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold

Sue LovegroveBeautiful Firetail, Stagonopleura bella, 2015watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold -

Sue LovegroveBlack Currawong, Stepera fuliginosa, 2016watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold

Sue LovegroveBlack Currawong, Stepera fuliginosa, 2016watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold -

Sue LovegroveSuperb Lyrebird, Menura novaehollandiae, 2016watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approx

Sue LovegroveSuperb Lyrebird, Menura novaehollandiae, 2016watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approx -

Sue LovegroveMantiq al-tayr, Language of the birds, 2016watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold

Sue LovegroveMantiq al-tayr, Language of the birds, 2016watercolour, gouache, ink, traditional pigments and 23 carat shell gold on old Indian manuscript paper, framed21 x 15 cm approxSold