Tim Burns: PAINTING THE SILENT MUSIC

Significantly, while Burns’s is very much an art of place, it is of place distilled, and clarified. Colour and light emulsify. The rich, encrusted red-browns are at once rusted iron and crusty tree-bark, the swept grey-greens blued steel and eucalyptus foliage.

4’ 33”

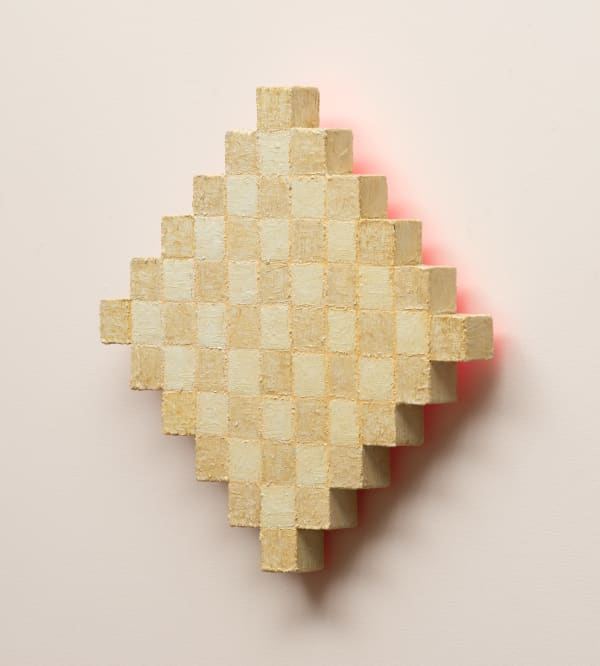

They come as a shock. They are beautiful and intriguing and confounding. The experience is is a bit like that of first seeing the James Webb Telescope’s photograph of the galaxy cluster SMACS 0723 as it was 4.6 billion years ago. These new works by Tim Burns not only defy expectations, but they also seem somehow à rebours, against history, against nature. They hover weightlessly in front of the gallery walls, framed by psychedelic backlighting, by a nimbus of pure colour.

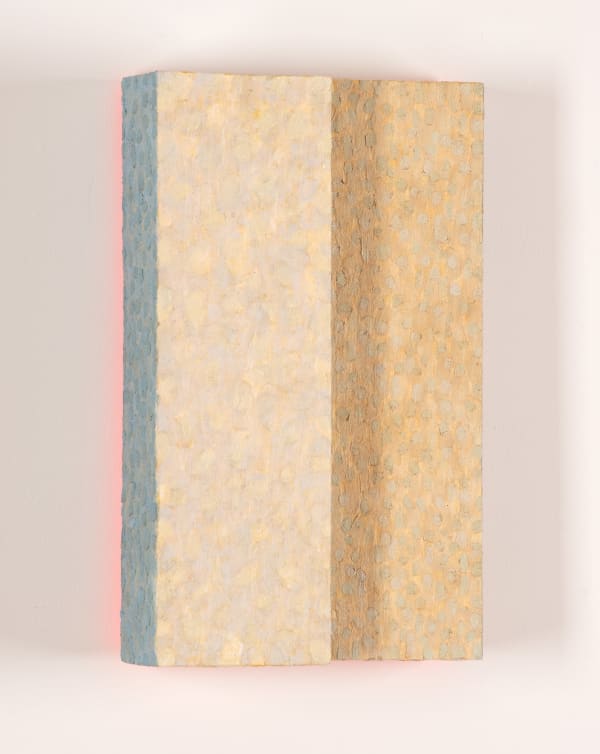

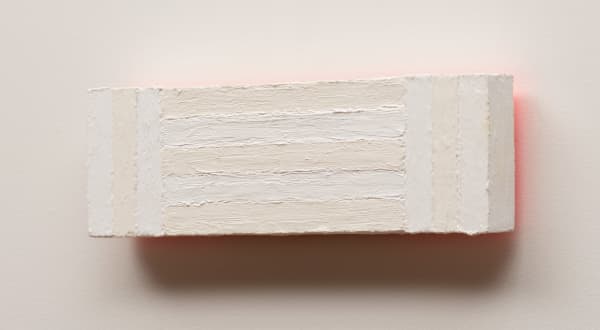

The lolly-pink halo is one of two devices or discoveries through which the artist deconstructs and reconstructs the practice of painting, both the medium as a whole - at least as it stands within the compass of Western, post-Renaissance art - and his own extensive oeuvre. The other surprising element in this new sequence is more solid, is in fact more carpentry-structural. The majority of the works are painted not on stretched canvas, but on solid wood: on panels, blocks and even narrow sticks. These things are made, fabricated, joined; they are constructed objects as much as painted surfaces. Sections jut into space, elements butt closely together, sides and fronts change place or value. They are sculptural paintings, paintings moving towards sculpture.

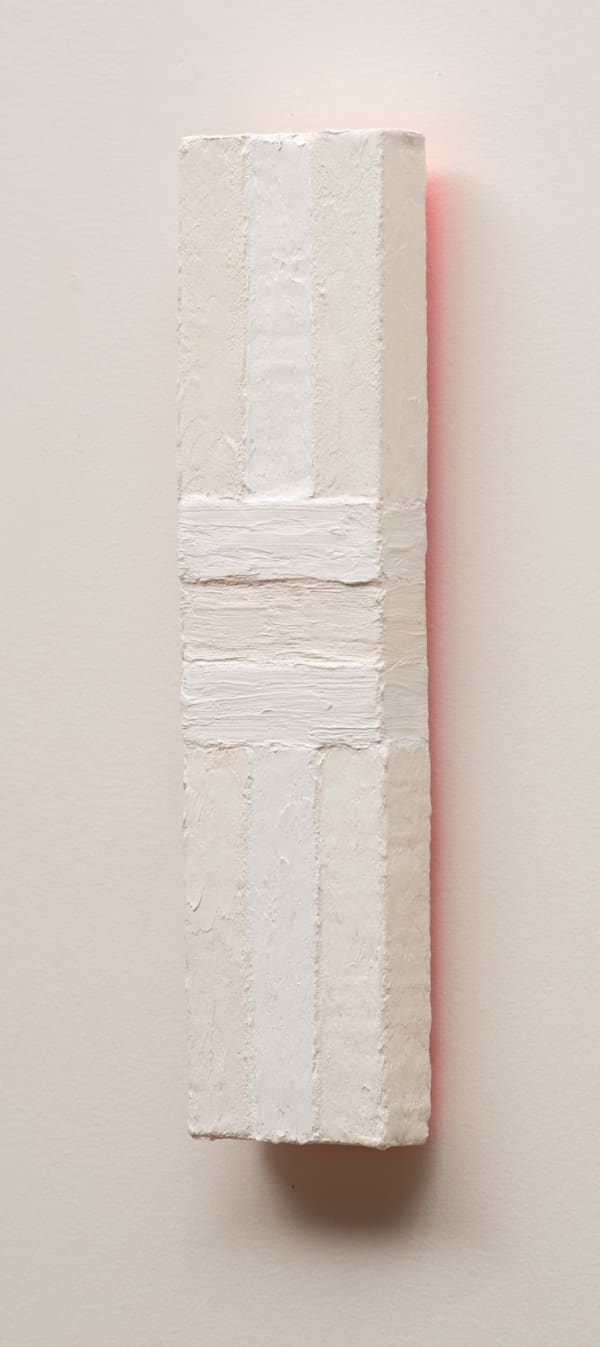

To this extent, Burns is working a claim first explored in post-war American painting: in the subtle, complex, epistemological ambiguities and expansions of Robert Rauschenberg’s ‘blank’ canvases and ‘combine’ paintings, in Jasper Johns’s flags and targets, or in the work of Frank Stella and the mid-1960s abstractionists, who shaped their canvasses away from the conventionally rectilinear, making parts of their surfaces project beyond the ground plane. While generally speaking flat planes and right-angle slab construction predominate, a couple of the new works are strict, mathematically-regular Cuisenaire-rod constructions, slightly reminiscent of Sol LeWitt’s white grid ‘structures.’ A couple of them are subtly chevron-surfaced, with fronts like fans or roof-ridges; with these it is hard to tell whether the tonal variation between their vertical bands comes from the paint colour or the modelling, the shadow or the substance.

Yet all this overt, unapologetic experimentalism, the works’ novelty value, is a means, not an end. The two major technical shifts have developed and work together in close formation. The roseate evanescence that thrums around the margins prompts the viewer to come closer, closer, to see how the effect is achieved, how the painting-object is constructed. In so doing, they will necessarily discover and examine (up close, very close) those various and variant surfaces that are the musical ground of Burns’s art. The subtly rich, layered accretions of pigment, the stroked and pushed and dashed and dotted surfaces reverberate not only with the time and care of making, but with soft, clear, harmonious echoes of tradition.

On a table in Burns’s studio is a postcard showing a close, very close detail of Rembrandt’s Man with a Golden Helmet, picked up during a recent residency in Berlin. Burns has always been attuned to such painterliness, to the fat impasto, with glazes over the top soft-colouring and soft-toning the valleys of each brushstroke, just as he has been to the coloured confetti and hundreds and thousands of the French Pointillists and Neo-Impressionists, and to the Zen-imperfect, labour-maximal minimalism of Agnes Martin.

Martin once said ‘we all have the same concern, but the artist must know exactly what the experience is. He must pursue the truth relentlessly.’ This statement brings us to another important dimension of Burns’s work, the one that is in some ways most obvious (and certainly most often discussed): the environment, the natural world, the landscape, the view, and most particularly wilderness: Tasmania, Bruny Island, the artist’s hermitage at Cloudy Bay. An insistent local truth certainly infuses his work, even at its most apparently self-sufficient, its most eye-candyish, it most mutely abstract. In his light-touched surfaces we see the translucent silver haze of spindrift, the wavelet splinters of sunshine on broad water, the running horizontals of the growling surf, the jostling, whispering verticals of the pine-tree plantation just behind the artist’s studio.

Significantly, while Burns’s is very much an art of place, it is of place distilled, and clarified. Colour and light emulsify. The rich, encrusted red-browns are at once rusted iron and crusty tree-bark, the swept grey-greens blued steel and eucalyptus foliage. Even the hi-vis haloes express a synthesis of multiple truths, sensual, experiential, emotional: the quotidien reality of a square cut in the studio wall left over from building work, through which the light from the hallway glows at night; a particular memory of the neon horizon of Berlin’s nightscape; the torn-cloud back-lighting of sunsets viewed across the d’Entrecasteaux Channel; the soft, warm light of a change coming in across the water.

David Hansen

Hobart

July 2022

Tim Burns is a notable figure in contemporary Tasmanian painting. Living and working at Cloudy Bay on Bruny Island, his scapes are of a less familiar kind than perhaps one would expect. Cannily referent far beyond his picturesque surrounds, Burns’s works capture more than the geographic and the built, the physical or the cultural, more even than the transitioning weather, capturing instead something like transition itself.

Of surprising scale and variation, Burns’s abstract works drift impossibly between Expressionist joy and Japanese minimalism. Texture, depth and detail shift subtly beneath simple, organic lines and forms. At times they are map-like, at others almost hieroglyphic; there is something ancient in the pictographic markings. The eye traces, rests and returns lyrically, boldly and peacefully.

Burns' works are held in numerous museum collections including the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Art Gallery of New South Wales, National Gallery of Victoria, Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery and the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. Burns is a winner of the Hobart Art Prize, 1994 and Fleurieu Biennale Art Prize in 2008.

Email the gallery to be placed on the preview list for this exhibition

-

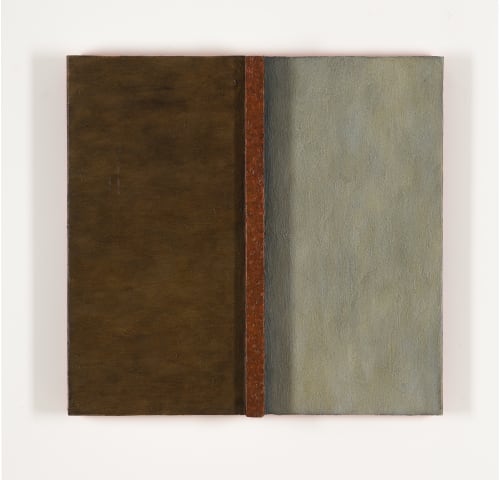

Tim BurnsPavane, 2022oil on wood80 x 80 x 5 cmAU$ 6,400.00

Tim BurnsPavane, 2022oil on wood80 x 80 x 5 cmAU$ 6,400.00 -

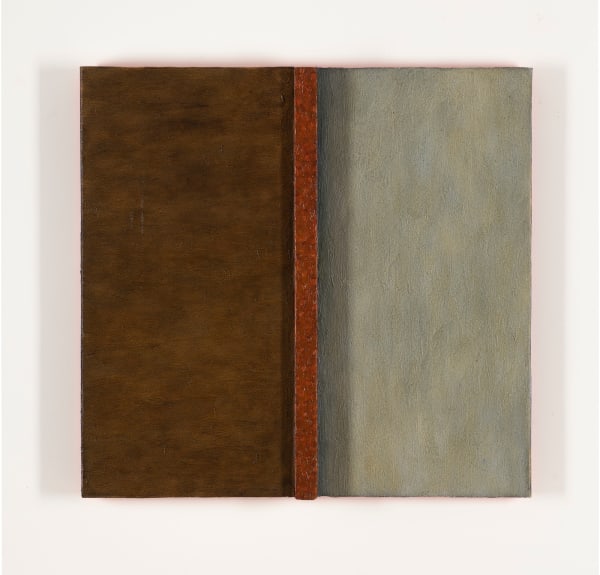

Tim BurnsThe authority of silence, 2022oil on wood92 x 62 x 5 cmAU$ 6,200.00

Tim BurnsThe authority of silence, 2022oil on wood92 x 62 x 5 cmAU$ 6,200.00 -

Tim BurnsThe sound is carved from the silence, 2022oil on wood61 x 63 x 6 cmAU$ 5,200.00

Tim BurnsThe sound is carved from the silence, 2022oil on wood61 x 63 x 6 cmAU$ 5,200.00 -

Tim BurnsChant in D minor, 2022oil on wood80 x 30 x 11cmSold

Tim BurnsChant in D minor, 2022oil on wood80 x 30 x 11cmSold -

Tim BurnsSilence is where questions are answered, 2022oil on wood40 x 40 x 10cmAU$ 3,800.00

Tim BurnsSilence is where questions are answered, 2022oil on wood40 x 40 x 10cmAU$ 3,800.00 -

Tim BurnsOn the edge of worldlessness, 2022oil on wood40 x 40 x 10cmAU$ 3,800.00

Tim BurnsOn the edge of worldlessness, 2022oil on wood40 x 40 x 10cmAU$ 3,800.00 -

Tim BurnsWhen words fail, 2022oil on wood40 x 40 x 8cm

Tim BurnsWhen words fail, 2022oil on wood40 x 40 x 8cm -

Tim BurnsSome songs undo me, 2022oil on linen41 x 41 x 2cmAU$ 3,600.00

Tim BurnsSome songs undo me, 2022oil on linen41 x 41 x 2cmAU$ 3,600.00 -

Tim BurnsSarabande, 2022oil on wood28.5 x 45 x 8.5cm

Tim BurnsSarabande, 2022oil on wood28.5 x 45 x 8.5cm -

Tim BurnsA musical silence, 2022oil on wood44 x 28 x 10cmSold

Tim BurnsA musical silence, 2022oil on wood44 x 28 x 10cmSold -

Tim BurnsComposition in white and cream, 2022oil on linen30 x 41 x 2.5cmAU$ 3,200.00

Tim BurnsComposition in white and cream, 2022oil on linen30 x 41 x 2.5cmAU$ 3,200.00 -

Tim BurnsThe pause determines the action, 2022oil on linen36 x 36 x 2.5cmAU$ 3,200.00

Tim BurnsThe pause determines the action, 2022oil on linen36 x 36 x 2.5cmAU$ 3,200.00 -

Tim BurnsSilent night, 2022oil on wood43 x 20 x 12cmAU$ 3,200.00

Tim BurnsSilent night, 2022oil on wood43 x 20 x 12cmAU$ 3,200.00 -

Tim BurnsSilence, 2022oil on wood33 x 30 x 10cmAU$ 3,200.00

Tim BurnsSilence, 2022oil on wood33 x 30 x 10cmAU$ 3,200.00 -

Tim BurnsInternalize the silence, 2022oil on wood30.5 x 31 x 12cmAU$ 3,200.00

Tim BurnsInternalize the silence, 2022oil on wood30.5 x 31 x 12cmAU$ 3,200.00 -

Tim BurnsDuet, 2022oil on wood39 x 18 x 12cmSold

Tim BurnsDuet, 2022oil on wood39 x 18 x 12cmSold -

Tim BurnsRhythm and blues, 2022oil on wood29.5 x 34 x 8 cmAU$ 3,000.00

Tim BurnsRhythm and blues, 2022oil on wood29.5 x 34 x 8 cmAU$ 3,000.00 -

Tim BurnsRaga, 2022oil on wood33 x 33 x 4.5cm

Tim BurnsRaga, 2022oil on wood33 x 33 x 4.5cm -

Tim BurnsChanson, 2022oil on wood40.5 x 18 x 10cmAU$ 3,000.00

Tim BurnsChanson, 2022oil on wood40.5 x 18 x 10cmAU$ 3,000.00 -

Tim BurnsThe colour of sound, 2022oil on linen31 x 31 x 4.5cmAU$ 2,800.00

Tim BurnsThe colour of sound, 2022oil on linen31 x 31 x 4.5cmAU$ 2,800.00 -

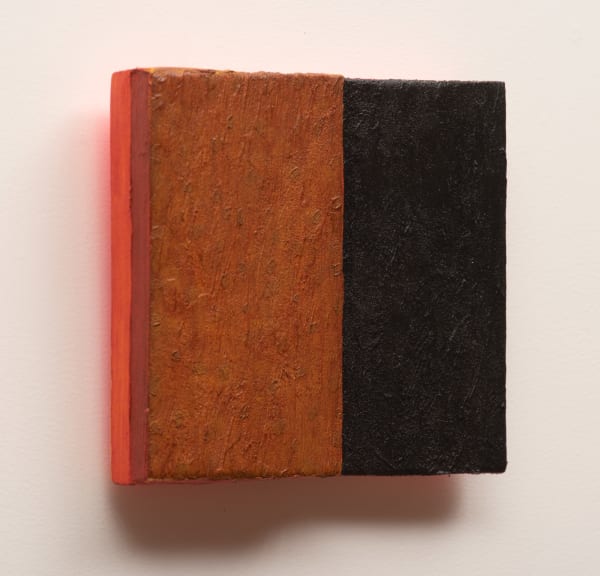

Tim BurnsFantasia in orange and blue, 2022oil on wood38.5 x 21 x 6cmAU$ 2,800.00

Tim BurnsFantasia in orange and blue, 2022oil on wood38.5 x 21 x 6cmAU$ 2,800.00 -

Tim BurnsSolo, 2022oil on wood120 x 3.5 x 3.5cmAU$ 2,600.00

Tim BurnsSolo, 2022oil on wood120 x 3.5 x 3.5cmAU$ 2,600.00 -

Tim BurnsThe security of rhythm, 2022oil on wood20 x 25.5 x 7.5 cmAU$ 2,400.00

Tim BurnsThe security of rhythm, 2022oil on wood20 x 25.5 x 7.5 cmAU$ 2,400.00 -

Tim BurnsTransient, 2022oil on wood26 x 16 x 8cmSold

Tim BurnsTransient, 2022oil on wood26 x 16 x 8cmSold -

Tim BurnsSolo 2, 2022oil on wood58 x 4 x 5 cmAU$ 2,200.00

Tim BurnsSolo 2, 2022oil on wood58 x 4 x 5 cmAU$ 2,200.00 -

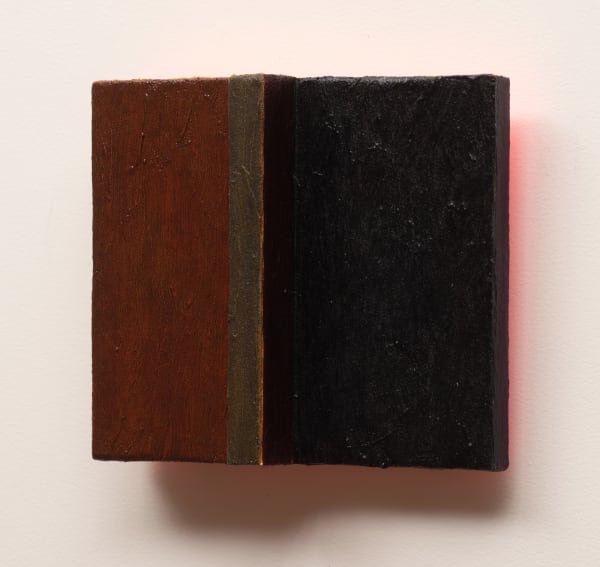

Tim BurnsHarmony in black and brown 2, 2022oil on wood18.5 x 22 x 6 cmAU$ 1,800.00

Tim BurnsHarmony in black and brown 2, 2022oil on wood18.5 x 22 x 6 cmAU$ 1,800.00 -

Tim BurnsHarmony in brown, 2022oil on wood16 x 21 x 4.5cmAU$ 1,800.00

Tim BurnsHarmony in brown, 2022oil on wood16 x 21 x 4.5cmAU$ 1,800.00 -

Tim BurnsHarmony in black and brown 1, 2022oil on wood18.5 x 22 x 4cmSold

Tim BurnsHarmony in black and brown 1, 2022oil on wood18.5 x 22 x 4cmSold -

Tim BurnsHarmony in blue and brown, 2022oil on wood18.5 x 22 x 4cmSold

Tim BurnsHarmony in blue and brown, 2022oil on wood18.5 x 22 x 4cmSold -

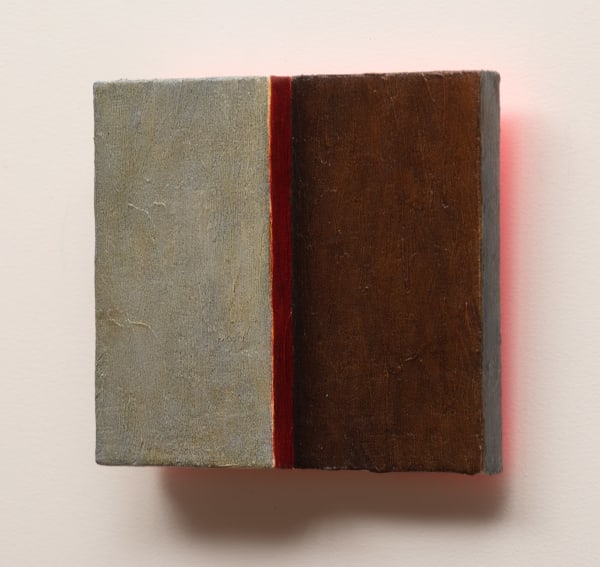

Tim BurnsHarmony in cream and grey, 2022oil on wood17 x 20 x 5cmSold

Tim BurnsHarmony in cream and grey, 2022oil on wood17 x 20 x 5cmSold -

Tim BurnsSong 1, 2022oil on wood28.5 x 7 x 3cmAU$ 1,600.00

Tim BurnsSong 1, 2022oil on wood28.5 x 7 x 3cmAU$ 1,600.00 -

Tim BurnsSong 2, 2022oil on wood9 x 28.5 x 4.5 cmSold

Tim BurnsSong 2, 2022oil on wood9 x 28.5 x 4.5 cmSold