Worry Doll - A Book Launch

Worry Doll foreword

Reason can be such a thin veil: paper-thin, retina-thin, so easily warped, ruptured and scrawled upon by the irrational. We know this every time we close our eyes to sleep, allowing our minds to wander and the pillars of language to tumble upon groundless space. In the words of Goya, El sueño de la razón produce monstruos: the sleep of reason brings forth monsters, a phrase since applied to many broad human conditions, from religious ignorance in 18th century Spain to contemporary political rallies. Just open a newspaper. That said, every artistic image, no matter how profound or allegorical or politically apt, begins with a personal moment of solitary daydreaming, as I’m sure it did for Goya, playfully doodling bats and owls cavorting over his own slumped figure at the desk. ‘Carumba!’ I imagine him thinking, ‘Maybe this craziness really means something…’

Our primary nightmares are personal, so much so that few things are harder to communicate in the light of day and outside of their own weird context. The sheer irrationality of them is beyond waking words. And it’s this very irrationality that frightens us the most. Not monsters or enemies, spiders, snakes or mortifying social situations, not even the dark: the worst stuff has no label at it, it’s the thing we can’t explain, the thing that erodes the very foundations of sense and language, the boundaries of self and other, the stable reality we all tacitly crave and perhaps too often take for granted.

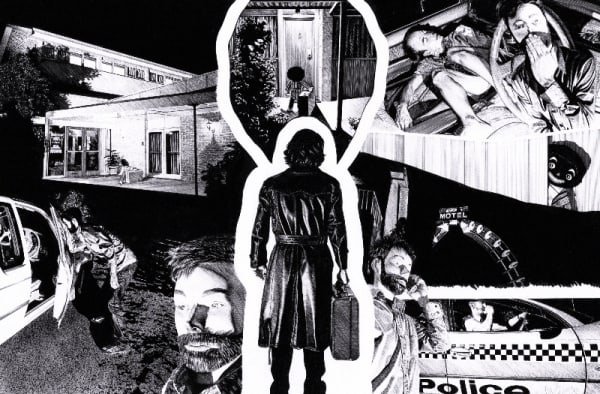

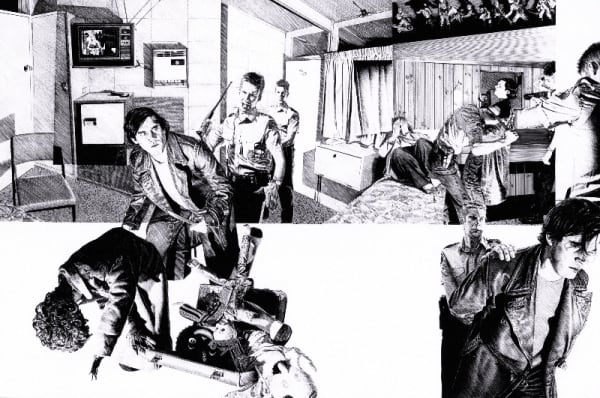

Enter a group of mismatched dolls wandering through stark suburban and rural landscapes, somehow dredged from an unconscious well and pinned to the bright white page for all to consider. And worry about. The first thing I noticed when I came across this stunning book was the sheer condensation of clinically precise black marks, hand-rendered with what I thought might be common artline pens. Which they were, it turned out, and moreover without any digital safety net, or corrective white-out for that matter. While most other readers might approach an illustrated book wondering what the story is about, as an illustrator – another of that strange breed that wilfully chooses to spend hours hunched over a desk, preferably in the dead of the night – I first and foremost look at the marks. Like any technician, I have a special fondness for the elementary particles of my profession, and it is lines above all other elements that seem to indicate commitment to an idea, the authority of artistic conviction, especially when the subject of a painting or illustration is actually evasive. Nobody I know does line-work – or evasive subject matter – like Matt Coyle. His scenes are rendered with such deftness and precision in one of the most unforgiving of all drawing media, where the smallest error or fickle hesitation sings out like a scratched record. And just like the grooves of a record, Matt’s use of hatching, those fine parallel lines that delineate contour and tone, never lapse into cross-hatching (where lines intersect) it’s more forgiving offspring, which most illustrators, including myself, gladly fall upon when things get woolly. It’s a technique that brings to mind those arts since lost to industrial and digital print processes, particularly engraving – think Gustave Dore – the secrets of which where often guarded by practitioners, as if by a guild of magicians. What is the fascination with this line-work, both for the creator and a reader? Why choose such a simple yet difficult medium for the expression of a complex vision?

I’m guessing that Matt might answer this question the way I do, that the question itself misses an important point. We don’t really choose a style or medium, rather it seems to choose us: it happens to align with a vision, to the extent that form and content seem to be one and the same thing. It somehow bottles time and feeling and thought (this was certainly my own intuition while working on meticulous pencil drawings for my own graphic novel, The Arrival). And this is where artistic conviction comes from, I think, realising that a voice and a song, a mark and its effect, are one and the same thing, relating to what the sculptor Henry Moore called ‘truth to materials’. The artist respectfully becomes something of a cipher, a medium, a conduit. In the case of Worry Doll, the union of thought, ink and paper is astounding, fascinating and commensurately unsettling.

While it’s easy to describe a mediocre visual narrative, of the kind we are subjected to everyday via ubiquitous media, to describe an excellent one is almost impossible: it’s language defies any substitution, it cannot be circumscribed. It cannot be given a sufficient written foreword for that matter. Which is not to say that I don’t have a complex interpretative reaction to Worry Doll as a story, if I can call such a novel piece of visual sequencing a ‘story’ in any conventional sense, I just don’t want to presume that my personal reading is worth your time, or is in any way aligned with your own. The best stories evade such fixed interpretation and Worry Doll is no exception. Yet deep below the surface, there is some inexplicable unity and purpose, a strange current that we all know and understand. It’s the same thing that drives an artist to draw and write peculiar fiction, often at significant personal cost, because conventional communication doesn’t quite cut it.

I’ll also refrain from writing as much as I’d like about the graphic innovations of this work, and why it must be regarded as one of the most significant illustrated narratives of recent years, in any genre, bar none (and like many other readers, I’m particularly thankful to both Dover and Mam Tor for publishing such innovative work, which is too rare a thing these days). Suffice to say, I keep returning to study the layouts, image framing and narrative omissions and wilful discrepancies like a student researching a thesis on the subject: insets, slicing and splicing, weird temporal shifts, negative spaces, I could go on and on. They stream out with apparently effortless ingenuity and resolve, as if merely witnessed, while I know from personal experience these scenes are anything but; that every composition is a matter of careful deliberation. And then there are all the minute details, from foliage to skin, car doors, fabric hemlines and decapitated dachshunds – could one say lovingly rendered? A better word might be forensic. Every piece of stark evidence only reminds us that all the things we really want to see are impossible to exhibit: the human psyche, the soul, reasons and motives. Words, our flimsy go-to guide for meaning, only serve to draw us deeper into a tangled paradox.

And rightly so. Matters of the soul are best left untold, invisible and unillustrated. They are rather evoked, you might even say dreamt: the writer or artist pressing our collective triggers and subconscious associations using whatever materials are to hand, trying to conjure some kind of pervasive feeling that we can ferry back into consciousness. In Worry Doll that feeling is strong, infectious, even hypnotic: a sort of trembling clarity, a charged atmosphere of the sort you might experience in a recurring nightmare.

You know the one. At first everything seems fine. Ordinary objects remain ordinary objects, nothing is especially hidden from view and the sun shines down neutral and benign, even a little too brightly. The landscape is familiar: familiar houses, gardens, streets, this should be comforting or banal, and either way, unremarkable. And yet all is tense with unrest, trembling in stillness, screaming in silence, and the closer you look, the more you can’t help but realise that your own eyes are nothing more than a thin and watery membrane, a layer of reason so easily punctured. Turn up the contrast, distil every outline, step away to examine the stark patterns of black and white, all to no avail. The world only flattens out like a picture on a page, framed by nothingness, and it’s getting really, really hard to breath. And, god help you, here come those dolls again… and there’s nothing you can do but look and worry, and turn page.

Shaun Tan, August 2015

-

Matt CoyleRecounting the events, 1999pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper30 x 45 cmAU$ 4,000.00

Matt CoyleRecounting the events, 1999pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper30 x 45 cmAU$ 4,000.00 -

Matt CoyleMy Friends are a Couple of Classics, 1998pen on paper, framed36.5 x 55.5 cmAU$ 5,150.00

Matt CoyleMy Friends are a Couple of Classics, 1998pen on paper, framed36.5 x 55.5 cmAU$ 5,150.00 -

Matt CoyleThe Living Room, 2007archival digital print on paper, unframed75 x 113 cm (image size)AU$ 1,500.00

Matt CoyleThe Living Room, 2007archival digital print on paper, unframed75 x 113 cm (image size)AU$ 1,500.00 -

Matt Coyle“Oh gosh! Whatever will we do?”, 1999pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper30 x 44 cmAU$ 4,000.00

Matt Coyle“Oh gosh! Whatever will we do?”, 1999pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper30 x 44 cmAU$ 4,000.00 -

Matt CoyleThe big wide world, 1999pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper33 x 50 cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt CoyleThe big wide world, 1999pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper33 x 50 cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

Matt CoyleWorking through it, 1999pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper31 x 45cmAU$ 4,000.00

Matt CoyleWorking through it, 1999pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper31 x 45cmAU$ 4,000.00 -

Matt CoyleSetting Out, 1998pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed30 x 45cmSold

Matt CoyleSetting Out, 1998pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed30 x 45cmSold -

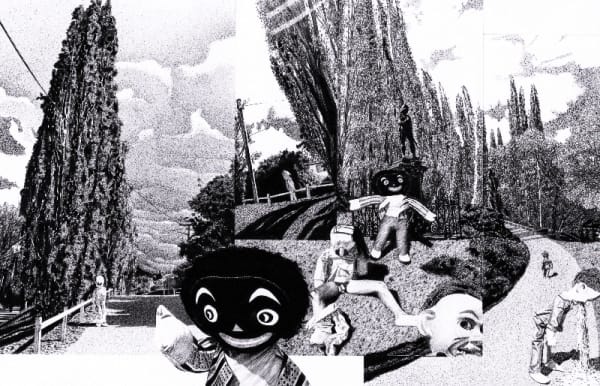

Matt CoyleFun in the Park, 1998pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper33 x 49cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt CoyleFun in the Park, 1998pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper33 x 49cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

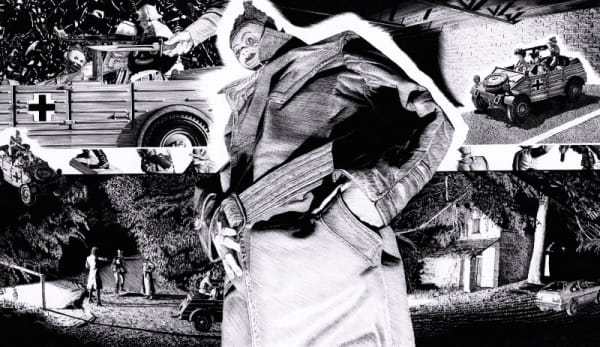

Matt CoyleIn the grip of something, 1999pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper33 x 51 cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt CoyleIn the grip of something, 1999pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper33 x 51 cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

Matt Coyle“I don’t know what possessed me”, 2002pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper38 x 49 cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt Coyle“I don’t know what possessed me”, 2002pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper38 x 49 cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

Matt Coyle“Our car’s arrived”, 2002pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper31 x 49.5 cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt Coyle“Our car’s arrived”, 2002pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper31 x 49.5 cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

Matt CoyleThe mysterious driver, 2002pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper32 x 45 cmAU$ 4,000.00

Matt CoyleThe mysterious driver, 2002pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper32 x 45 cmAU$ 4,000.00 -

Matt CoyleTime out/Taking stock, 2001pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper35 x 52.5 cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt CoyleTime out/Taking stock, 2001pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper35 x 52.5 cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

Matt CoyleGetting into the bush, 1999pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper27.5 x 42.5 cmAU$ 3,800.00

Matt CoyleGetting into the bush, 1999pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper27.5 x 42.5 cmAU$ 3,800.00 -

Matt CoyleNight vista, 2005pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper35 x 53 cmAU$ 3,800.00

Matt CoyleNight vista, 2005pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper35 x 53 cmAU$ 3,800.00 -

Matt CoyleShow us the way please, 2005pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed36 x 62 cmAU$ 5,500.00

Matt CoyleShow us the way please, 2005pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed36 x 62 cmAU$ 5,500.00 -

Matt CoyleA sense of disquiet, 2001pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper30 x 55 cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt CoyleA sense of disquiet, 2001pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper30 x 55 cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

Matt CoyleConcerning developments, 2001pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper35.5 x 52 cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt CoyleConcerning developments, 2001pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper35.5 x 52 cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

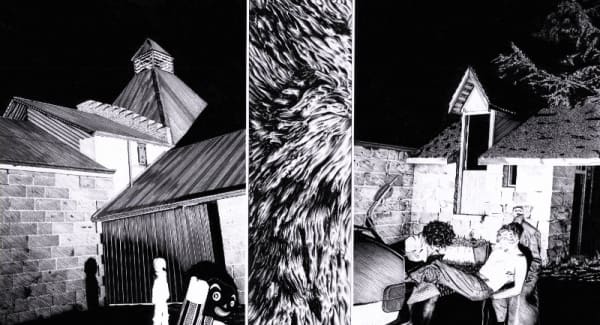

Matt CoyleConfrontation in the coach house, 2000pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed38 x 52 cmAU$ 5,200.00

Matt CoyleConfrontation in the coach house, 2000pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed38 x 52 cmAU$ 5,200.00 -

Matt CoyleAn awakening, 2001pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed35 x 55 cmAU$ 4,800.00

Matt CoyleAn awakening, 2001pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed35 x 55 cmAU$ 4,800.00 -

Matt CoyleHitching, 2001pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed32 x 52.5 cmSold

Matt CoyleHitching, 2001pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed32 x 52.5 cmSold -

Matt CoyleAn offer of a ride, 2000pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed33 x 60.5 cmAU$ 4,800.00

Matt CoyleAn offer of a ride, 2000pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed33 x 60.5 cmAU$ 4,800.00 -

Matt CoyleThe Elm Motel, 2002pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed36 x 54 cmSold

Matt CoyleThe Elm Motel, 2002pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed36 x 54 cmSold -

Matt CoyleHoming in, 2003pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed35 x 53 cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt CoyleHoming in, 2003pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed35 x 53 cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

Matt CoyleA reunion, 2002pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed30 x 52 cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt CoyleA reunion, 2002pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed30 x 52 cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

Matt CoyleA salesman at the door, 2004pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed35 x 53 cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt CoyleA salesman at the door, 2004pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed35 x 53 cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

Matt CoyleIt had been an eventful few days, 2003pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed35 x 51.5 cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt CoyleIt had been an eventful few days, 2003pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed35 x 51.5 cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

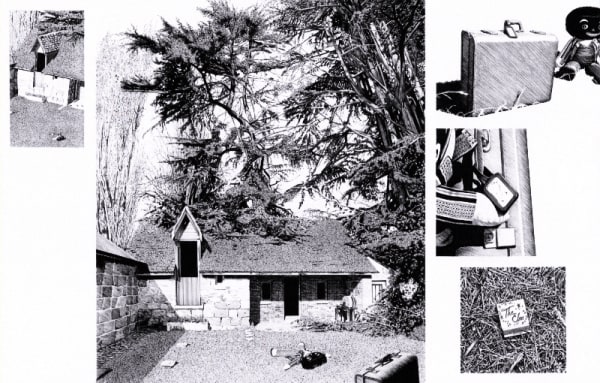

Matt CoyleThe suitcase, 2003pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed32.5 x 49 cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt CoyleThe suitcase, 2003pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed32.5 x 49 cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

Matt CoyleArrested, 2005pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed36 x 54 cmAU$ 4,800.00

Matt CoyleArrested, 2005pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed36 x 54 cmAU$ 4,800.00 -

Matt CoyleThe resident, 2004pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed33 x 52 cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt CoyleThe resident, 2004pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed33 x 52 cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

Matt CoyleClosure, 2004pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed32 x 49 cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt CoyleClosure, 2004pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper, framed32 x 49 cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

Matt CoyleExcess luggage, 2003pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper,33 x 55cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt CoyleExcess luggage, 2003pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper,33 x 55cmAU$ 4,400.00 -

Matt CoyleAnother opening, 2004pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper,33 x 52 cmAU$ 4,400.00

Matt CoyleAnother opening, 2004pure pigment ink on Arches 300gsm paper,33 x 52 cmAU$ 4,400.00