We are making a new world

LOVE WALKS NAKED

RICHARD FLANAGAN

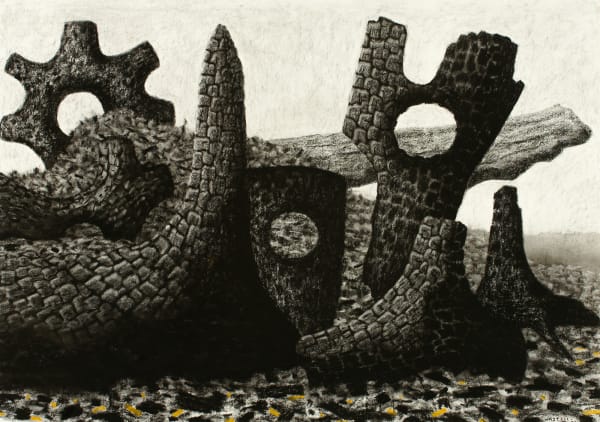

Cruel Tasmania, an island of secrets, threats, lies; of an often pitiless exploitation of both its own land and its own people, has wounded Richard Wastell into an extraordinary response—a series of beautiful paintings and drawings inspired by the ongoing clearfelling of Tasmania’s old growth forests.

For in Tasmania forest unlike any other in the world continues to be levelled to the ground to produce woodchips. After being industrially logged, what remains is napalmed from the air to produce fires of such intense ferocity that the resultant fireballs resemble atomic cloud mushrooms. Into the plains of ash that are left are planted monocultural plantations, maintained by an intense regime of poisoning and fertilising that has seen protected native animals killed in their hundreds of thousands, water supplies poisoned, and the spectre of a raft of illnesses draughting in the wake of these horrendous practices.

To maintain such monstrosity, to evade the ever growing public anger, the woodchipping industry has had to exercise an ever stronger control over ever more aspects of Tasmanian life. Both major parties in Tasmania, and much of the Tasmanian media frequently give the appearance of existing only as a client of the woodchippers. State interest and those of this industry are now so thoroughly identified as identical that anyone questioning the woodchipping industry’s actions is attacked by leading government figures as a traitor to Tasmania. And not only the forest has been destroyed by this industry. Its poison has seeped into every aspect of Tasmanian life: jobs are threatened, careers destroyed, people driven to leave.

All this is background, but necessary background to these paintings. After firebombing, what was once forest is transformed into an extraordinary ruined landscape, which, if not of conventional sylvan beauty, still has about it a spectacular power rarely seen outside of the battlefields of great wars. Parts of the Styx valley, which has been the particular inspiration for these paintings, brings to mind images of Passchendale and the Somme, with their mud and ash and charred and twisted trees.

Though they will have forever after in Tasmania an undeniably political dimension, these are anything but political paintings. They are intensely spiritual paintings by a painter whose close technique becomes ever more capable of conveying an enormous emotion.

And perhaps this is because the particular agony of Tasmania is in the end neither environmental nor political but spiritual, and it is merely one end, one highly visible end, of a continuum that extends from the muddy ash of the Styx valley to the blood spattered walls of Baghdad and the torture cells of Guantanamo Bay.

Could it be for this reason that in these paintings of clearfelled forest coupes, there can be divined images of torment and destruction of wider resonance? That in these charred man ferns and twisted regnans can be sensed not only the bodies of the slain of our new age of terror, but the guiding spirit of this age—the horrific consequence of having allowed ourselves to capitulate to lies promulgated by the powerful?

You can daily read much about this world in the newspapers, follow its vicissitudes and horrors on a hundred cable news programs and a thousand radio broadcast and an infinite number of podcasts. But if you wish to know the truth about our times, I doubt you could do little better than look at these extraordinary paintings.

I don’t mean to say that such grand ideas formed the ambition of this exhibition, which was conceived to deal with seemingly limited matters: landscapes, textures, shapes, form, composition. Painterly matters. But they do form its considerable achievement. Somehow, as good art always does, these paintings have escaped the artist’s necessarily narrow intentions.

There is about them the pain of enormous rupture, the sense of an irredeemable despair. No solace ought be taken from either the exhibition’s ironic title (echoing the famous Paul Nash painting of the same name depicting a World War I battlefield) , nor such paintings as 'Who Pays the Ferryman? (Styx Valley, 2006)’ where a few hard waterferns are a promising green amidst the bituminous black that so dominates this exhibition. This is Tasmania, not Europe. The great forests are gone, and they will not return, and nor will the intense human response we had to such places. Everything hereafter will be ordered and imaginable, paintable and representable in a way that those wild places never were, and we will be less.

These paintings represent something new in Australian painting: they mark the point where we finally acknowledged our connection with the land in the most profound way possible: by acknowledging the spiritual cost of its destruction. Though it is beyond my capacity to pass judgement on this exhibition, I suspect that in the future it will come to be regarded as a landmark in Australian painting in its rendering of the desolation with which our era feels itself beset.

These paintings’ beguiling simplicity belies their profound artistic and intellectual influences. The Entombment for example, takes both its name and composition from Caravaggio’s painting, as does The Betrayal. In the former, instead of Christ we have a charred regnans embraced by other incinerated trees.

As Caravaggio brought a new subject to art, the dirty and dissolute street people of his time, and imbued the beggars and prostitutes and urchins with a radiant humanity, so does Richard Wastell give the charred manferns and regnans and celery tops an unexpected majesty.

There is a certain odd courage in all this, a refusal to seek solace in any fashionable depictions. This is steely eyed observation of the world as it is. The painstaking technique is evident in each finely rendered charcoal square, every charred lichen circle, in the determination to discover the world as it is, to strip it back to its fundamental truths through rendering of the most basic elements: mud, ash, smoke, charcoal.

As an exhibition this does not have the reassuring sense of the familiar. Nor does it offer the reassurance landscapes so often have, no matter how different the aesthetic. But we live in a world that has deliberately shed itself of almost everything that reminds people of their impermanence, their fragility, their capacity and need for transcendence. Nothing is left to balance the horror of life. Power and money are what are to be admired as water vanishes, as seas rise, as forests fall, as life atrophies: except when it can be bought and consumed, beauty is to be despised and the contemplation of the world decreed as a sickness, depression, maladies.

Power and money are to be all that remains, and politics is what ensures this is so. Politics places man at the centre of life, and in permanent opposition to the universe. Love, to the contrary, fills man with the universe. The history of love is a record of the need to assert the idea of love against the force of history. Art, at its best, is the chronicle of that history.

Richard Wastell’s subject for this exhibition was forlorn, but still he painted these pictures. Why? It seems not uncoincidental that as he was painting these pictures his partner, Rosemary, was expecting their first child. Perhaps as he embarked on the ultimate gamble of this life, that of being a parent, he sensed that love is no guarantee. Maybe it is this that lends the paintings their terrible and despairing force, for against the extraordinary resources greed and power can now galvanise, against the lies and horror which we must now daily swallow as bread, this collective portrayal of a universal, inescapable agony seems only the more oppressive for the quality of its execution.

And yet this would not be the whole truth. The act of creative courage these paintings represent, the fact of their existence, suggests an opposite force at work in their making. The poet Rilke observed that true works of art can not be apprehended through criticism, but only through love, because that is the impulse out of which they arise. There is a naked truth about these paintings, and if I had to give a name to this exhibition, I would call it ‘Love Walks Naked.’

For love is never enough, but it is all we have.

RICHARD FLANAGAN, June 2006.

-

Richard WastellThe betrayal (for Caravaggio), 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 122w cmSold

Richard WastellThe betrayal (for Caravaggio), 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 122w cmSold -

Richard WastellThe Hard-Water Fern, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 122w cmSold

Richard WastellThe Hard-Water Fern, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 122w cmSold -

Richard WastellWatchman, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 122w cmSold

Richard WastellWatchman, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 122w cmSold -

Richard WastellThe price of my soul , 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 122w cmSold

Richard WastellThe price of my soul , 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 122w cmSold -

Richard WastellWho pays the ferryman? (Styx Valley), 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 122w cmSold

Richard WastellWho pays the ferryman? (Styx Valley), 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 122w cmSold -

Richard WastellNapalm forest. Myrtle, Leatherwood, Sassafras, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 182w cmSold

Richard WastellNapalm forest. Myrtle, Leatherwood, Sassafras, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 182w cmSold -

Richard WastellMonster fields, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 182w cmSold

Richard WastellMonster fields, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 182w cmSold -

Richard WastellBlack roots, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 182w cmSold

Richard WastellBlack roots, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 182w cmSold -

Richard WastellEntombment (for Caravaggio), 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 182w cmSold

Richard WastellEntombment (for Caravaggio), 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 182w cmSold -

Richard WastellThe wild beasts, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 182w cmSold

Richard WastellThe wild beasts, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 182w cmSold -

Richard WastellForest mound of ash, charcoal and mud, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 182w cmSold

Richard WastellForest mound of ash, charcoal and mud, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 182w cmSold -

Richard WastellThen Tasmania can be a shining beacon, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 182w cmSold

Richard WastellThen Tasmania can be a shining beacon, 2006Oil & marble dust on linen132h x 182w cmSold -

Richard WastellMonster fields (study), 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold

Richard WastellMonster fields (study), 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold -

Richard WastellMounds of ash, charcoal and mud, 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold

Richard WastellMounds of ash, charcoal and mud, 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold -

Richard WastellSun through autumn smoke, 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold

Richard WastellSun through autumn smoke, 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold -

Richard WastellTwo logging coupes, 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold

Richard WastellTwo logging coupes, 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold -

Richard WastellBurnt forest forms , 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold

Richard WastellBurnt forest forms , 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold -

Richard WastellMound of ash, charcoal and mud at night, 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold

Richard WastellMound of ash, charcoal and mud at night, 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold -

Richard WastellNight studio, Rome, 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold

Richard WastellNight studio, Rome, 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold -

Richard WastellEmbers, smoke and the strange light of dawn, 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold

Richard WastellEmbers, smoke and the strange light of dawn, 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold -

Richard WastellThe wild beasts (study) , 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold

Richard WastellThe wild beasts (study) , 2006Charcoal & pastel on paper, framed86 x 122cmSold