Raymond Arnold: Body Armour / Char Corps

In the summer of 1997 Raymond Arnold visited the Historial de la Grande Guerre museum in Péronne, France. While viewing the display of machine guns, rifles and trench mortars from WW I, he came across a ‘tunic-waistcoat’ of dark suiting fabric and pin-striped silk, armoured on the front with a solid but flexible screen of square metal plates. It was labelled ‘Abdominal protection for a British soldier’. Although Arnold was struck by the odd combination of businessman-like formality and armoured protection (for the costume seemed both pathetically vulnerable and touchingly homespun) he also realised that the vest would have been a powerful talisman for the wearer—in battle this symbol of enduring family love, hearth and home could stir the courage of a lion and make the soldier feel truly invincible.

Recently, at the War Memorial in Canberra, a sound and light show of a Second World War air attack gave me some idea of what my father had experienced in battle, but it was a diorama of a seated wireless operator mannequin facing his station which allowed me to stand right behind the figure’s shoulder, that was the most powerful evocation of the real. Not only could I say to myself—my father wore gloves just like these, leather jacket, flying cap, boots, all just like these—but I could also imagine his fear as he sat in that tiny vibrating space in the bitter cold and dark, and as a gunner, calling ‘Left–left–mind the flak’ as he waited to be blown to bits like his friend.

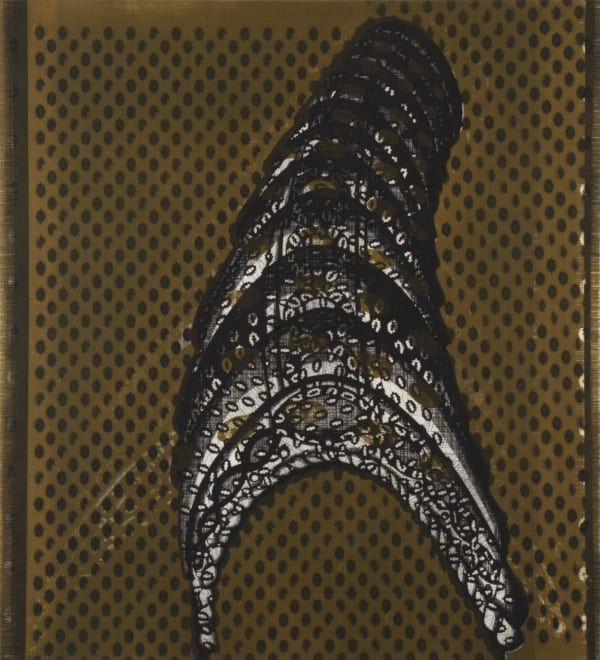

Arnold stitched small squares of cheap lace material together to suggest the Péronne vest in the Memory/History’s Body Armour/Char Corps print. The copperplate was aligned with a perforated zinc plate of cross motifs to metaphorically integrate an individual figure into the body of the army/corps:

‘The folding of the figure into the ground is a singular pictorial strategy which I carried on from the ‘And For Each Sense…’ series of prints, and it mirrors a multiple, if not infinite, series of personal catastrophes.’ The dual mirror format, which suggests the images can turn in on themselves, like bodies being folded into the earth, is a significant theoretical and emotional device. Early on Arnold noted that paper being peeled from an inked copperplate fascinatingly mirrored the plate image. The artist harnessed this effect in Memory/History and built on it, re-using plates twice for repeated effects, and in the later Henri and Bayeux Soldat series, created composite images from two plates, based on twinned figure and ground relationships. All series take on dual French and English titles, as befits the artist’s peripatetic ‘post-modern’ existence in two hemispheres. This life has allowed Arnold to braid himself into the work, so in France, a place where he has no real roots, and where he can be anything, the artist virtually becomes his subjects, like Kafka’s beetle; he is in turn Henri IV, the soldier ghosts and the Bayeux soldiers.

When Raymond Arnold showed me a WW I tunic in the Australian War Memorial covered in dried mud on the same day as my encounter with the radio operator mannequin, again I experienced something powerful. In this case, the Somme soil, that is, the landscape itself, was adhered to the already poignant coat. What had its wearer seen and experienced to be covered by so much caked earth? Had he died in battle? Or did he survive the war and keep the jacket as a reminder of his good fortune and his comrades’ sacrifices?

‘The embroidered images of Norman knights in the Bayeux Tapestry museum are duplicated and amplified by a cavalcade of soldier mannequins at the D-Day museum nearby. My small two-plate images are drawn in situ in the WW 2 museum and the larger two-plate etchings are subsequently developed from these initial investigations over time at my Paris workbench. This method of precedence or notation, anticipating a type of construction, underpins my strategy. The museum sourced small image precedes and is, in turn, amplified by the physicality of ink and paper of the larger printed sheet. This transition confirms an exchange where the image could be said to be ‘morphing’ or folding back into materiality – back into the object!’

Home from Canberra, I take Arnold’s Bayeux Soldat V print from the drawer, remove the tissue and look at the image of the life–sized soldier’s chest, aware that it mirrors my own beating one. The torso is a kind of stage, and the rich and lively interplay of buckles, buttons, metal rings, shoulder straps and flourishes of cloth are like melodramatic actions in an operatic tragedy; the frenzy all at once highlights the discomfort of soldiers as walking targets and harnessed mules — full of outward bravado and inward fear — and the futility of armour and cloth as bodily protection. I think of the function of skin as a divider of zones—just as delicate surface tension separates sky and water, so too does the barrier of flesh contain our bodies and separate our inner body from our outer. The disarray of the kit that lies upon the soldier’s skin in one sphere is echoed by the warm, tangled entrails, heart and lungs attached inside the body in another.

-

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - L’épaulière droite, 2001etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15 plus 2 artist's proofsAU$ 2,500.00

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - L’épaulière droite, 2001etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15 plus 2 artist's proofsAU$ 2,500.00 -

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - Le cuissard droit, 2001etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15AU$ 2,500.00

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - Le cuissard droit, 2001etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15AU$ 2,500.00 -

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - La jambière gauche, 2001etching on paper, framed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15 plus 2 artist's proofsAU$ 2,500.00

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - La jambière gauche, 2001etching on paper, framed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15 plus 2 artist's proofsAU$ 2,500.00 -

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - Le plastron, 2002etching on paper, unframed

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - Le plastron, 2002etching on paper, unframed

92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15 plus 5 artist's proofsAU$ 2,500.00 -

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - Le deuxième gant, 2003etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15 plus 2 artist's proofsAU$ 2,500.00

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - Le deuxième gant, 2003etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15 plus 2 artist's proofsAU$ 2,500.00 -

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - Mainfaire, 2003etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15 plus 2 artist's proofsAU$ 2,500.00

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - Mainfaire, 2003etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15 plus 2 artist's proofsAU$ 2,500.00 -

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - Volante, 2003etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15 plus 2 artist's proofsAU$ 2,500.00

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - Volante, 2003etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15 plus 2 artist's proofsAU$ 2,500.00 -

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV – La deuxième cubitière, 20032 wo-plate colour etching on 270gsm Velin Arches paper, unframed70 x 63cm (image) 92 x 63cm (sheet)Edition of 15AU$ 2,500.00

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV – La deuxième cubitière, 20032 wo-plate colour etching on 270gsm Velin Arches paper, unframed70 x 63cm (image) 92 x 63cm (sheet)Edition of 15AU$ 2,500.00 -

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - Le gant droit, 2001etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15 plus 2 artist's proofsAU$ 2,500.00

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - Le gant droit, 2001etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15 plus 2 artist's proofsAU$ 2,500.00 -

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - Le casque, 2001etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Suite 1Sold

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - Le casque, 2001etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Suite 1Sold -

Raymond Arnold, Henri IV - La jambière droite, 2002

Raymond Arnold, Henri IV - La jambière droite, 2002 -

Raymond Arnold, Henri IV - Renfort de l’épaulière, 2002

Raymond Arnold, Henri IV - Renfort de l’épaulière, 2002 -

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - La cubitière gauche, 2002etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15 plus 2 artist's proofsAU$ 2,500.00

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - La cubitière gauche, 2002etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)Edition of 15 plus 2 artist's proofsAU$ 2,500.00 -

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - La cuirasse partie arrière, 2002etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)AU$ 2,500.00

Raymond ArnoldHenri IV - La cuirasse partie arrière, 2002etching on paper, unframed92h x 63w cm (sheet size)AU$ 2,500.00