Balance Point

Minimum Curvature. The circle perfectly represents Platonic idealism: static and complete, beyond time and space. Uninfluenced by the vexatious forces and contingencies that confound the mundane, the circle symbolises heaven eternal. Rotated through 360 degrees, the circle produces a sphere, a figure almost as closed and inscrutable as its progenitor. The perfection, however, of circle and sphere is vulnerable. Pull it, push it, distort it - break the line or the surface - and eternity is banished and a history, however fleeting, is implied.

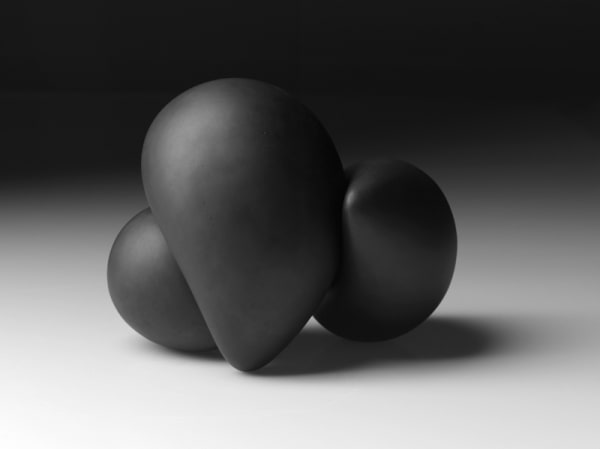

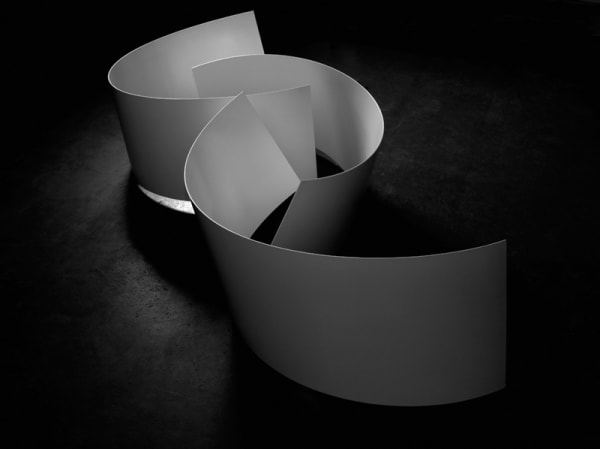

Belinda Winkler’s sculptural forms hover at this moment of minimal and potential narrative. The tension, compression and distortion expressed in the curvature of edges and surfaces imply a history of the application of force and therefore the passage of time, but the work itself supplies nothing more than this. The viewer reads into the contraposto curves and twisting surfaces the strain of muscle and tendon, the tautness of stretched skin or the effects of gravitational force. It may be biophilic empathy that leads us to read these works as organism. The larger scale of Winkler’s rolled steel pieces renders them anthropomorphic, suggesting the surfaces and actions of a human body.

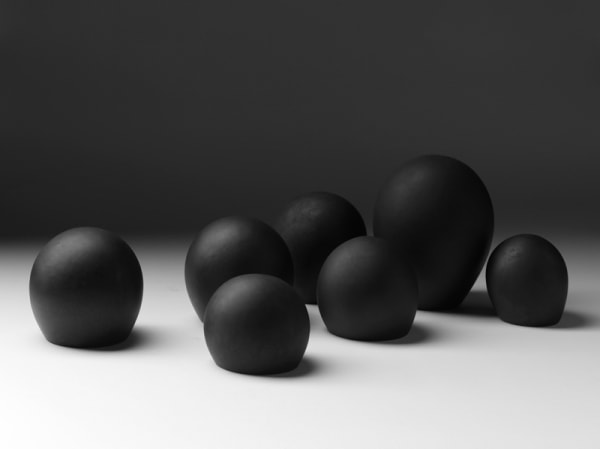

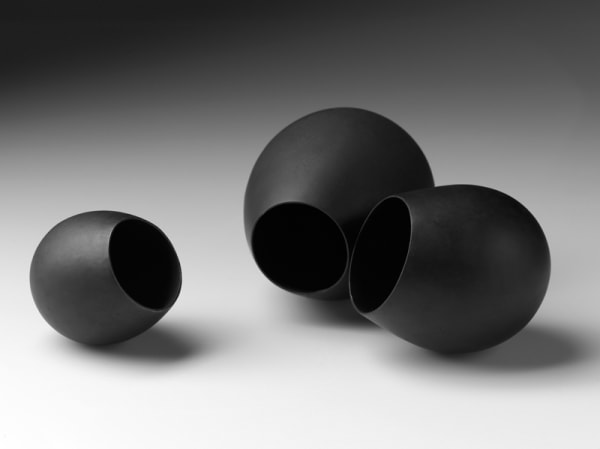

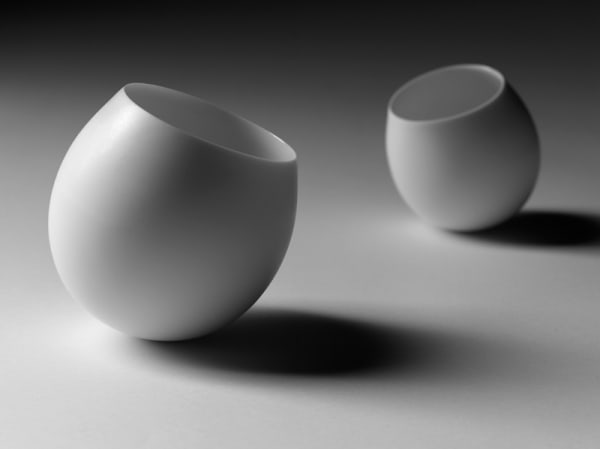

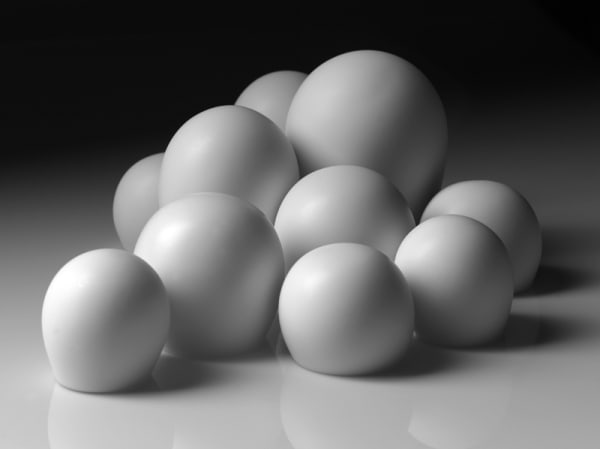

With her closed and semi-closed vessel forms Winkler explores her biotic minimalism in a different way. Their full, subtly asymmetrical shape alone renders them broadly biomorphic, especially when they are clustered as groups and pairs in implicit communion. Here, the silhouettes of the forms suggest specific relationships - intimacy, tension, need, maybe nurturing. The spaces between, where the surfaces draw infinitely close, sing with potential energy. The openings in the forms, which we cannot help but read as mouths, extend this biomorphism, its size alone transforming their characters. Poised between organism and vessel, large openings suggest generosity or hunger, smaller ones perhaps disregard or sufficiency. Forming these openings with a precise, planar slice through the form, Winkler references Euclidean geometry and emphasizes the illusory nature of our biophilic readings.

The smooth, perfect finish of Winkler’s work serves both to emphasise the skin-like qualities of the surfaces and to eliminate a competing narrative of fabrication. The life seemingly inherent in the curves and shapes of her forms is far from the anaemic, indeed Platonic, perfection of cyberspace. To achieve her minimum curvature Winkler’s methods are emphatically analogue; she experiments with metal, foam, creepy fabrics such as Lycra®, liquid-filled balloons and other materials; compressing, stretching, running them through industrial bending and rolling machines. At this stage, roughly cut plywood shapes bolted through sheets of foam, liquid-filled balloons distorted with string and scaly bands of rolled steel are far from the smooth, sensuous and sometimes erotic surfaces that Winkler achieves in the finished work. Yet it is these processes that, through experiment, repetition and serendipity, produce curves and surfaces with the spring and tension that gives them life.

Twentieth century Minimalist sculptors sought to eliminate the anthropomorphic and with it extraneous narrative from their work. At the edge of the minimal, Winkler’s work conducts a stripped down potential for narrative, exploiting our almost inevitable tendency to see meaning in form and life and movement in the curve.

Peter Hughes

Senior Curator (Decorative Arts)

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

-

Belinda WinklerEncounter #6, 2011solid cast bronze & hollow cast bronze2 objects: 11 x 16 x 11 cm (approximate installation size)

Belinda WinklerEncounter #6, 2011solid cast bronze & hollow cast bronze2 objects: 11 x 16 x 11 cm (approximate installation size)

edition of 3Sold -

Belinda WinklerEncounter #5, 2011solid cast bronze & hollow cast bronze2 objects: 8 x 14 x 11 cm (approximate installation size)

Belinda WinklerEncounter #5, 2011solid cast bronze & hollow cast bronze2 objects: 8 x 14 x 11 cm (approximate installation size)

edition of 3AU$ 3,300.00 -

Belinda WinklerEncounter #7, 2011hollow cast bronze18 x 23 x 16 cm (overall size)

Belinda WinklerEncounter #7, 2011hollow cast bronze18 x 23 x 16 cm (overall size)

edition of 3Sold -

Belinda WinklerAlight #2, 2011hollow cast bronze12 x 12 x 12 cm (overall size)

Belinda WinklerAlight #2, 2011hollow cast bronze12 x 12 x 12 cm (overall size)

edition of 3AU$ 2,500.00 -

Belinda WinklerCounterbalance, 2011solid cast bronze & hollow cast bronze2 objects: 12 x 24 x 12 cm (approximate installation size)

Belinda WinklerCounterbalance, 2011solid cast bronze & hollow cast bronze2 objects: 12 x 24 x 12 cm (approximate installation size)

edition of 3Sold -

Belinda WinklerGravity #4, 2011hollow cast bronze2 objects: 12 x 24 x 12 cm (approximate installation size)

Belinda WinklerGravity #4, 2011hollow cast bronze2 objects: 12 x 24 x 12 cm (approximate installation size)

edition of 3Edition of 3 plus 1 artist's proofAU$ 4,400.00 -

Belinda WinklerBalance Point, 2011hollow cast bronze13 x 13 x 13 cm (overall size)

Belinda WinklerBalance Point, 2011hollow cast bronze13 x 13 x 13 cm (overall size)

edition of 3AU$ 2,200.00 -

Belinda WinklerGravity #5, 2011solid cast bronze7 objects: 21 x 45 x 35 cm (approximate installation size)

Belinda WinklerGravity #5, 2011solid cast bronze7 objects: 21 x 45 x 35 cm (approximate installation size)

unique stateSold -

Belinda WinklerAlign, 2011hollow cast bronze5 objects: 12 x 65 x 12 cm (approximate installation size)

Belinda WinklerAlign, 2011hollow cast bronze5 objects: 12 x 65 x 12 cm (approximate installation size)

edition of 3AU$ 11,000.00 -

Belinda WinklerEncounter #4, 2011hollow cast bronze3 objects: 11 x 35 x 20 cm (approximate installation size)

Belinda WinklerEncounter #4, 2011hollow cast bronze3 objects: 11 x 35 x 20 cm (approximate installation size)

edition of 3AU$ 6,500.00 -

Belinda WinklerEncounter #8, 2011hollow cast bronze3 objects: 15 x 25 x 20 cm (approximate installation size)

Belinda WinklerEncounter #8, 2011hollow cast bronze3 objects: 15 x 25 x 20 cm (approximate installation size)

edition of 3Sold -

Belinda WinklerGravitate #1, 2011Southern Ice Porcelain with glazed interior2 objects: 12 x 24 x 12 cm (approximate installation size)Sold

Belinda WinklerGravitate #1, 2011Southern Ice Porcelain with glazed interior2 objects: 12 x 24 x 12 cm (approximate installation size)Sold -

Belinda WinklerGravitate #2, 2011Southern Ice Porcelain with glazed interior3 objects: 85 x 30 x 30 cm (approximate installation size)Sold

Belinda WinklerGravitate #2, 2011Southern Ice Porcelain with glazed interior3 objects: 85 x 30 x 30 cm (approximate installation size)Sold -

Belinda WinklerEncounter #3, 2011Southern Ice Porcelain with glazed interior3 objects: 11 x 35 x 20 cm (approximate installation size)Sold

Belinda WinklerEncounter #3, 2011Southern Ice Porcelain with glazed interior3 objects: 11 x 35 x 20 cm (approximate installation size)Sold -

Belinda WinklerGravity #6, 2011Southern Ice Porcelain with glazed interior10 objects: 18 x 40 x 30 cm (approximate installation size)Sold

Belinda WinklerGravity #6, 2011Southern Ice Porcelain with glazed interior10 objects: 18 x 40 x 30 cm (approximate installation size)Sold -

Belinda WinklerContrapposto #1, 2011steel & polyurethane3 objects: 85 x 350 x 150 cm (approximate installation size)Sold

Belinda WinklerContrapposto #1, 2011steel & polyurethane3 objects: 85 x 350 x 150 cm (approximate installation size)Sold -

Belinda WinklerContrapposto #2, 2011steel & polyurethane2 objects: 100 x 270 x 80 cm (approximate installation size)Sold

Belinda WinklerContrapposto #2, 2011steel & polyurethane2 objects: 100 x 270 x 80 cm (approximate installation size)Sold